“Europe’s least populated northern regions were affected by the pandemic to the lowest extent”, remark the authors of the report, stressing that more than two year long struggle with the pandemic in Europe was in fact a collection of many totally different experiences depending on the region of residence.

The different intensity and duration of the pandemic created a kind of gap between the eastern and southern regions ‒ on the one hand, and the north and the west ‒ on the other. According to Eurostat surveys, more than every second citizen of Sweden, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Austria and Germany claimed that they or their close family and friends had not been personally affected by serious illness, a loss of a relative or a friend, or economic hardships. At the opposite end were respondents from the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Hungary and Poland.

Residents of southern European countries (Spaniards, Italians and Greeks) defined the socio-economic consequences of the pandemic in a similar way, despite the fact that COVID-19 hit them the most severely at the very beginning of the crisis. However, as these regions strongly depend on tourism, the shock which the tourist sector had experienced caused some economic turbulence, the consequences of which are still felt today.

“Central and Eastern Europe recorded the highest number of infections and deaths. At the same time, the economies of most of these countries, including Poland, coped with the crisis better than those of the West. This was partly due to the withdrawal of many European companies from Asia and their return to the continent. This has let them avoid a number of social problems (e.g., the rapid growth in unemployment among young people), which the >>EU15<< countries will be struggling with for years to come”, ESPON experts point out.

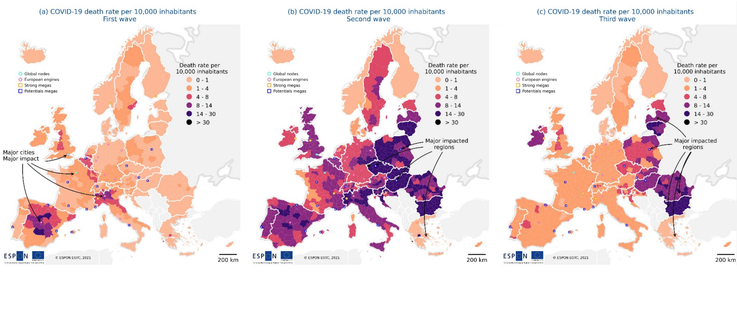

The analysis of mortality due to COVID-19 revealed that the first wave of the pandemic had hit major urban centres (Madrid, Paris, London or Milan), also acting as global transport hubs, as well as regions characterised by a high degree of mobility (French Moselle and Rhône, Italian Emilia-Romagna and Piemonte, and Spanish Ciudad Real, Toledo and Zaragoza).

“In an interconnected and integrated world, rich regions remain more open to international trade and movement of people. They are thus also more vulnerable to pandemics. The fact that Northern Italy was the first European region to be hit by the virus had resulted from the size of the Chinese diaspora living there, and from mobility between Milan and China. It is worth noting that Milan Malpensa, Italy’s second airport after Rome’s Fiumicino, had become the FedEx hub in Europe and one of the most important cargo airports in the south part of the continent”, ESPON experts stress.

In contrast, Central and Eastern European regions showed high immunity during the first wave – as COVID-19 had reached them several weeks later than the western part of the continent, the rigorous containment measures taken in a timely manner made it possible to reduce the spread of the virus.

“However, during the subsequent waves, the virus moved from Western Europe to Central and Eastern Europe, as a result of which the areas previously less affected by the pandemic became its main central points. High infection and mortality rates also persisted there for much longer periods than in most western European regions, leaving a deep mark on the collective pandemic experience”, the ESPON report remarks.

Europe is not a monolith, but rather a combination of very diverse regions ‒ this was already proven by some landmark events of the previous decade. The euro crisis roughly divided Europeans into a richer north and an indebted south, while attitudes towards migrants from the Middle East and Africa drew a new line of division between the east and the west. Even the support for Ukraine struggling with the Russian aggression, clearly visible in Poland and other EU border countries, is no longer so widespread in places far from the conflict centre, where the war is sometimes perceived merely from the perspective of ongoing economic interests.

In addition, hundreds of maps and studies from the extensive archives of ESPON, a programme funded by the European Commission to investigate the spatial development of Europe, reveal that significant differences in all aspects of social and economic life are present also, or perhaps primarily, within individual countries on the continent. After all, the European Union is made up not only of 27 countries, but also of 300 regions inhabited by over 400 million people.

The past two years were no exception — Europe’s efforts to contain COVID-19 are a tale of several different pandemics. Various regions of the continent were affected to a varied degree at different times, so the emotions and experiences of their inhabitants are dissimilar.

Source: PAP MediaRoom

Pochodzenie wiadomości: pap-mediaroom.pl